Europe, Ukraine Needs You

by u/ReasonRiffs

Abstract

Whilst the US shirks its commitment to European defence, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has entered its fourth year, devolving into a grinding contest of industrial capacity, morale, and political will. With the battlefield stretching from the Black Sea to the forests of the north, the decisive front in 2025 may be European arms factories, parliaments and public squares. This article quantifies Ukraine’s current and projected military shortfalls, assesses the reliability of the United States as a security partner, and evaluates whether European allies can, and will, extend and substantiate its support. Using data from the Kiel Ukraine Support Tracker, Eurobarometer polling and official NATO documents, we show that European rearmament, including Ukraine, is no longer optional: if Kyiv is allowed to fail, the long-run cost of deterrence will dwarf today’s support budgets.

The Shortfall: Ukraine’s Immediate Military Requirements

Over the past year, Ukraine has fired an average of 6,000 to 8,000 155 mm artillery shells per day on the eastern front — a rate that exceeds Western deliveries by approximately one-third [1]. A single infantry brigade defending the city of Avdiivka can burn through 30,000 rounds a month. Precision munitions tell a similar story: in April 2025, Kyiv exhausted an entire month’s supply of GMLRS rockets in just eleven days of counter-battery fire.

Illustrative gaps in training and ammunition for the forthcoming July–December period [2]

- 155 mm shells – 180,000 per month needed; 110,000 pledged (40% shortfall).

- Patriot missiles – 300 required; 120 pledged (60% shortfall).

- GMLRS rockets – 2,400 required; 1,050 pledged (60% shortfall).

- Trained infantry – 19,000 replacements requested; 11,500 available training slots (40% shortfall).

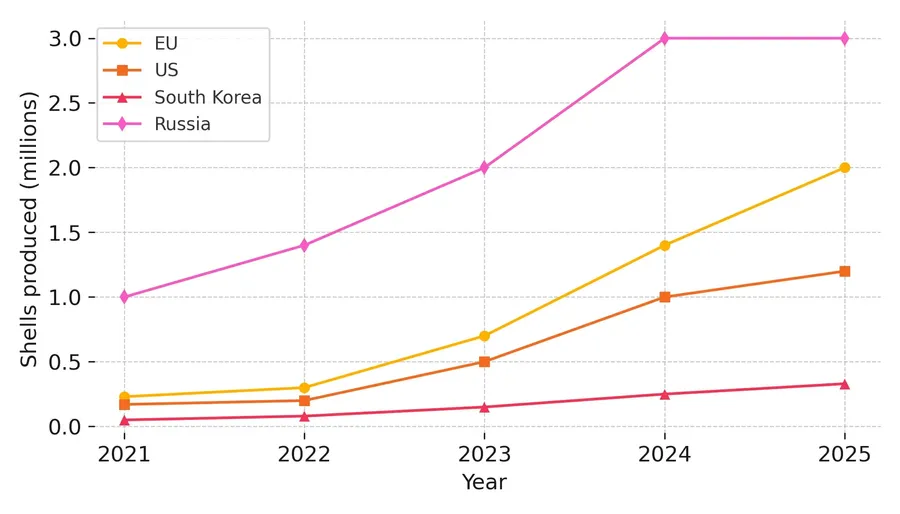

Ukraine also lacks at least four extra Patriot radars to cover Kharkiv and Odesa simultaneously. Even after the EU Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) pushed European output past one million rounds in 2024, total supply remains lower than Ukraine’s projected 2025 burn rate [3]. Unless the gap closes, Ukraine will be forced to economise fire or cede ground. Prior shortfalls and irregular support have led to some of the most significant Ukrainian withdrawals, notably from Avdiivka in February 2024. President Biden publicly stated that the withdrawal was “forced upon Ukraine by dwindling supplies as a result of congressional inaction” [4] [5].

Ukrainian forces were compelled to ration ammunition, with front-line units reportedly “armed only with assault rifles” after running out of artillery—Reuters described the conditions as “worse than hell” [6] [7]. President Zelenskyy characterised the Western pause in deliveries as an “artificial deficit” that “allows Putin to adapt to the current intensity of the war” [8]. These episodes not only cost Ukraine critical territory but also deeply affected morale at critical moments.

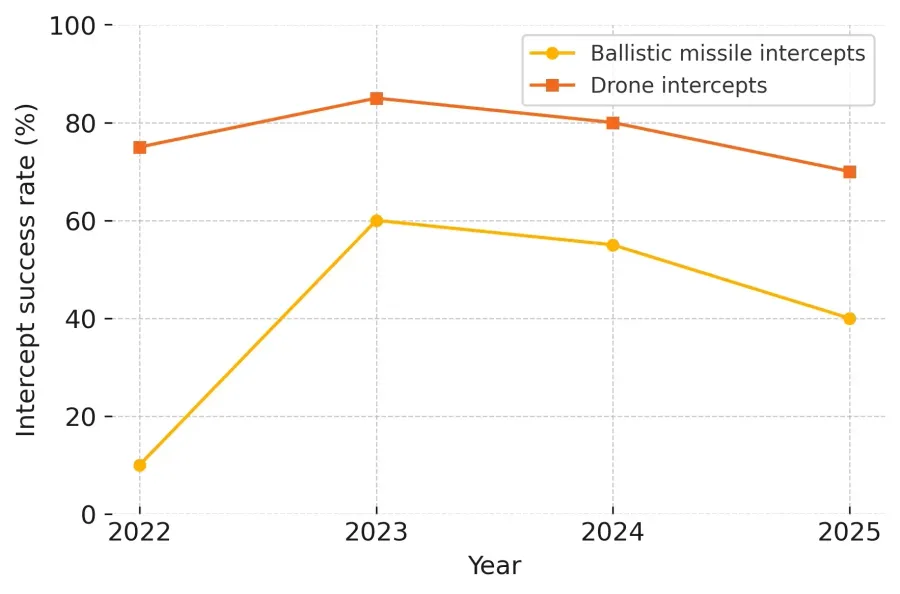

Ukrainian interception rates of Russian missiles and drone barrages, showing a decline from about 60% during 2023 to approximately 40% in recent months for ballistic and cruise missiles, while drone interception remained relatively higher at around 82%[9] [10]. In the case of the former, the drop in the average has been the result of concentrated coordinated, and increasingly sophisticated attacks lead to only a one in three inception rate.

The US, an Untrustworthy Partner

For all the talk of renewal, the Trump presidency has brought fresh uncertainty to U.S. policy toward Ukraine — a shift that has played into Russia’s hands and no doubt pleased President Vladimir Putin. In December 2024, as president-elect, Trump publicly called for an “immediate ceasefire” and pronounced the conflict a “madness” that must end now, yet he offered no actionable plan, creating confusion among Ukrainian leadership and NATO allies [11]. The fear of Trump’s intentions have often been confounded by his occasional praise, even recently, of Putin.

In recent weeks, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth again halted shipments of Patriot interceptors and other precision munitions in July 2025. This despite internal Pentagon assessments that U.S. stockpiles were sufficient and no indication Trump had approved the pause [12] [13]. Reports in The Guardian and from congressional Democrats assert Hegseth "falsely cited weapon shortages" and acted unilaterally, contradicting both Pentagon officials and the White House’s own review stating U.S. arsenals remain "unquestioned" in readiness [12] [14].

Indeed, the move surprised key figures in the Pentagon, State Department and Congress, many now question whether it reflects Trump’s direction or Hegseth’s personal agenda, especially as lawmakers push back and demand explanations for this erratic intervention.

In May 2025 Trump announced renewed ceasefire talks with both Putin and Zelenskyy, only for U.S. military aid to be halted days later due to unspecified stock take reviews, sending mixed signals to Kyiv [15] [16]. Likewise, after meeting Zelenskyy at The Hague in June, Trump signaled an openness to more Patriot missile deliveries. Yet, the Pentagon officially confirmed a pause in shipments looming in July—underscoring the erratic nature of U.S. support, not to mention contradictory messaging [17] [18].

As early as in February 2025, Hegseth froze outbound Patriot and GMLRS shipments for the first of these "stock-takes" [19] [20]. This suggests that Hegseth may have had more clout in the administration, and from an earlier point in time, than has been apparent on the surface. Moreover, if this were the case, it would hardly be surprising if further evidence emerged of other administration members leveraging their positions for personal agendas — with Trump concealing such behavior to maintain the appearance of control.

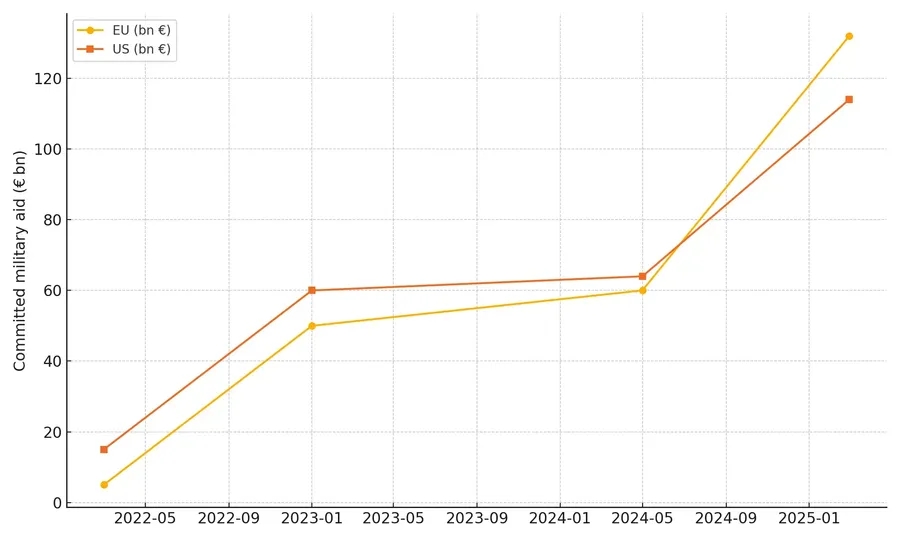

Financially, U.S. military commitments have plateaued at about €65bn, 25% below the late 2023 peak. Europe, by contrast, has climbed to €72bn and now exceeds the United States in net military aid [2].

The yo-yo pattern undermines operational planning in Kyiv and has convinced many European capitals that they must prepare to shoulder the bulk of the burden. At some point, the uncertainty of US support is arguably worse than no support at all.

What about Ukraine’s European Allies?

European pledges are rising, but delivery is uneven. Germany’s Bundeswehr reports that only 68% of promised Marder IFVs had cleared depots by May 2025 [21]. Southern states lag on air‑defence equipment. Italy’s Aspide launchers missed their hand‑over date by four months [22]. On the plus side, the Franco‑British Storm Shadow initiative was delivered two months early, and Poland has begun shipping home‑built Krab howitzers at a rate of four per month [23].

Money is also finally flowing. EU institutions have approved more than €35bn in macro-financial assistance and budget support [24], while lethal aid channeled through the European Peace Facility (EPF) has been recapitalized from €5.7 bn at launch to €17 bn in early 2025 [25]. That still trails U.S. Foreign Military Financing on paper, but—crucially—the EU funds are multi-annual, providing defence firms with far clearer demand signals.

Recent NATO figures show eleven allies already spend 2% of GDP on defence. The new Hague Summit pledge aims for 5% by 2035 [26]. If even half that delta is ring-fenced for munitions, Europe could underwrite Ukraine and rebuild its own stocks simultaneously.

European partners have demonstrated mixed reliability. Whilst bureaucratic delays and national politics have occasionally slowed arms delivery, their underlying commitment remains strong. A Reuters report noted that despite initial applause for joint EU armaments funding, several member states delayed actual shipments, yet none walked away from their pledges [27].

Moreover, Eastern European defense firms, particularly in Poland and the Czech Republic, ramped up shell production substantially, exemplifying tangible follow-through when called upon [28]. Analysis from the Atlantic Council also highlights that, though processes take longer than U.S. draw-downs, European contributions, including artillery, air defence, and logistical support, show persistent logistic and political engagement rather than faltering intention [29]. In short, delays have more to do with EU bureaucracy and capacity constraints than with wavering political will.

Limited European Stocks

If Ukraine’s European allies are reliable then why the hesitation in promising more? Most of Ukraine’s European allies are not hoarding weapons and ammunition for themselves. National inventories are paper-thin. Germany acknowledged in late 2024 that it held only 20,000 serviceable 155 mm shells – barely two days of Ukraine’s peak expenditure. Norway confesses to "under three wartime days" of high-explosive rounds, and Dutch Patriots are down to single-digit. A 2024 CSIS audit found that 17 of 31 NATO members failed the alliance guideline of 30 days of high-intensity stock.

Countries have scoured the globe for stop-gap shells. South Korea sold 200,000 rounds via private brokers, itself having ramped up production. India diverted 50,000 rounds through a Czech intermediary. Such ad-hoc buys fill holes but add layers of political dependency, delays, and cost.

In the longer term pre-existing stocks become replaced by new production. Thence, though initial commitments to Ukraine have been constrained by limited stocks, ongoing and additional commitments will reflect the realised expansion of Europe’s arms and ammunition production.

Elasticity of Production

Armaments output generally has low short-run elasticity, but the past two years prove it is not zero having seen quite a substantial increase in some cases. EU ASAP money lifted shell capacity from roughly 230,000 in 2021 to more than one million in 2024 [3]. Poland’s PGZ plans EUR 600 million to quintuple production to 180,000 rounds by 2030, and France’s Nexter added eight machining lines in Bourges. The Commission projects continental capacity could hit two million rounds in 2025 if long-term contracts materialise. That would satisfy Ukraine and allow allies to start rebuilding whilst far out-pacing the US’s own production.

Bottlenecks are shifting from steel casings to energetics. European propellant plants run at 95 percent capacity, and nitrocellulose is sourced from a single facility in Finland. A proposed European Propellant Act would subsidise new chemical lines and spread risk.

In a further sign of continental rearmament, Germany announced in July 2025 the purchase of an additional 105 Leopard 2A8 tanks, bringing its total procurement to over 200 [30]. The new models will enter service by 2027 and reflect Germany’s broader pivot toward sustained military investment. While these tanks may not directly reach Ukraine, their purchase releases older models for potential transfer, as seen with the 2023 donation of Leopard 2A4s.

Despite these advances, Europe still struggles to independently replace certain U.S. capabilities. Patriot missile production in Europe is increasing but remains tightly linked to American manufacturers. While Raytheon has begun doubling Patriot output in German facilities, with official plans to expand production capacity by 2028-2030 and a new GEM-T assembly plant under construction in Schrobenhausen, these are extensions of U.S. firms operating under European licenses [31] [32] [33].

Moreover, even as NATO champions joint missile initiatives, production timelines remain multiyear undertakings. Lockheed Martin and MBDA are scaling up PAC-3 and GEM‑T missile assembly, but independent European systems like the Franco-Italian SAMP‑T NG are only beginning to emerge, and still trail behind U.S. systems in deployment and scale [34] [35]. In short, while Europe is rapidly industrializing its air-defence assembly lines, it cannot yet replicate U.S. missile production, Patriot and related systems remain structurally tied to American industry for the foreseeable future.

Starlink, Elon Musk’s satellite internet system, remains a critical vulnerability. It is still without question critical to Ukraine’s war effort. Ukraine’s battlefield connectivity has repeatedly relied on the system, and no European alternative offers comparable bandwidth or decentralised coverage [36]. Intelligence-sharing, particularly satellite and signal intelligence, also remains lopsided. While Airbus and European Space Agency assets contribute, the bulk of tactical satellite data comes via NATO channels dominated by U.S. assets. Until domestic European systems expand significantly, these capabilities cannot yet be substituted.

One expansion of production is not based in Europe’s manufacturing centres. Europe can erase Ukraine’s training deficit by doubling the EU Military Assistance Mission’s goal from 75 000 to 150 000 graduates by mid-2026 [37]. Building on the UK-led Operation Interflex, which has already prepared 56 000 recruits [38], mobile multinational teams should shift courses to Poland, Slovakia and, when Kyiv agrees, western Ukraine-an option London is now exploring with Kyiv [39]. A train-the-trainer model backed by deployable simulators financed through the 2025 European Defence Fund would shorten absences from the front [40]. Specialist hubs such as Romania’s F-16 centre should expand intake to accelerate pilot conversion before donated jets arrive [41].

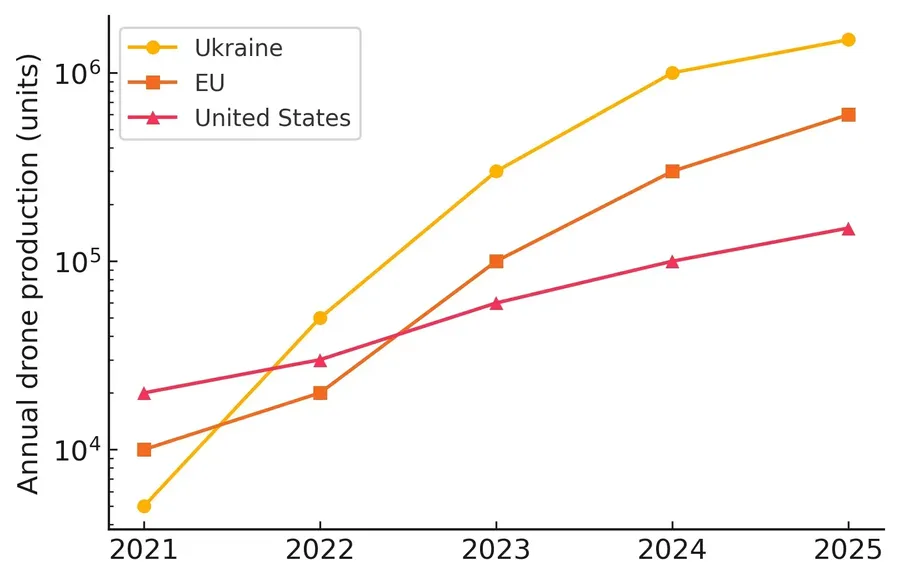

Indicative production of military-grade UAVs. Ukraine’s state-order programme expanded from a few thousand FPV drones in 2021 to ~1 million in 2024 and a planned 1.5 million in 2025 [42]. EU output reflects the "Drone Coalition" pledges and published contracts [43] [44], though substantially behind Ukraine are still ahead of the US, while U.S. numbers come from DoD FY-24/25 procurement tables for Switchblade 300/600 and Phoenix Ghost [45]. Drone production is ramping up substantially in all three cases. Log scale used for clarity.

Annual average estimates of 155 mm-class (EU / US / S. Korea) and 152 mm (Russia) artillery-shell output, 2021-2025. Like-for-like comparison is difficult between Russia and NATO production. Russian figures are the average estimate of 2-4 million shells. Russian shells are inherently less accurate. North Korea also has a substantial capability to produce 152mm shells but decent estimates are hard to come by. 2025 numbers are estimations though EU countries appear on target. [46], [47] [48], [49], [50][51], [52] [53]

Public opinion in Europe

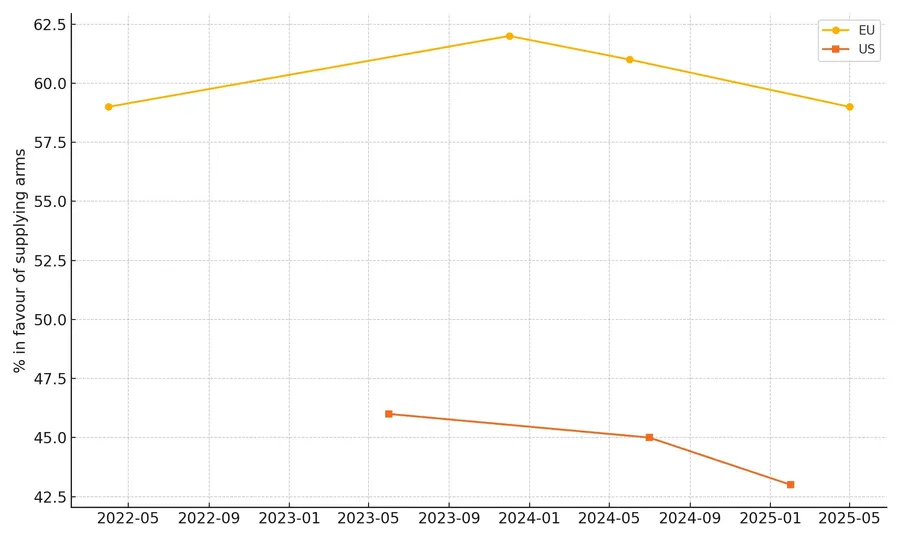

Wars are ultimately decided by politics. Eurobarometer 103 finds 59% of EU citizens still support financing arms for Ukraine, while 76% back non-arms financial aid [54]. Support exceeds 70% in Sweden, Portugal and Denmark but lingers below 30 percent in Hungary and Slovakia. The trend since 2023 shows a modest four-point decline – hardly the "Ukraine fatigue" some pundits predict.

Crucially, when asked whether national defence budgets should rise further if Ukraine is forced to cede territory, 68 percent across the EU say yes. Voters appear to recognise that the bill will come due one way or another, their preference is to pay it now at a discount recognising the return on investment.

Nevertheless, the divergent opinions of various EU nations renders the EU itself a challenging vessel for effective timely support. The advantage of pooling money as a group of nations as opposed to individual nations ensures access to far greater funds, given the lower risks involved and greater efficacy of shared goals. This has led to Brussels becoming the preferred channel, with individual European nations’ support in parallel. Collective EU aid packages have been financed through the European Peace Facility, ASAP shell-production scheme, the €50bn Ukraine Facility and other joint instruments [24] [27] [55].

When Budapest blocked a €6.5 bn EPF tranche in late 2023, other states back-filled bilaterally until the money was unfrozen, showing the joint channel can be paused but not killed [27]. This shows that the added challenge of bringing the least supportive nations to the table can be overcome, and that the average support across EU member states remains the most critical metric for gauging the durability of Europe’s backing for Ukraine [29].

Share of respondents who say their country should finance/supply military equipment to Ukraine. European support for Ukraine has remained solid and notably higher than in the US reflecting the differing commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty. EU data: Flash Eurobarometer 506 (Apr 2022)[56], Std. Eurobarometer 101 (Dec 2023)[57], Std. Eurobarometer 103 (May 2025)[58]. US data: Pew Research Center polls (Jun 2023, Jul 2024, Feb 2025)[59], [60], [61].

Cumulative face-value military pledges to Ukraine. EU nations (plus the UK) have overtaken the US in total military aid provided. Quarter-end snapshots from the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker[2] and Reuters tallies[62], [63]. Euro figures converted at contemporaneous ECB EURO/DOLLAR reference rates.

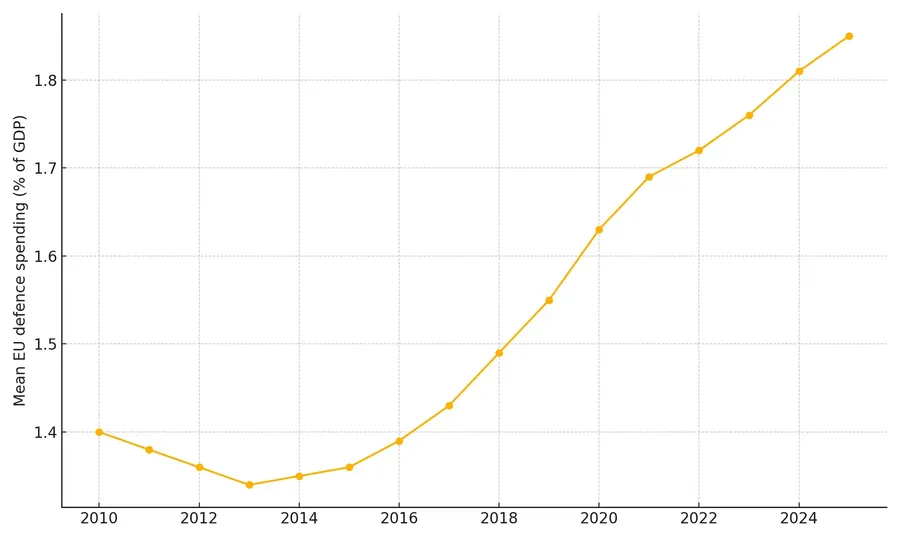

Mean defence expenditure of EU member states expressed as a share of GDP (current-price NATO definition). Interestingly the increase in spending can be observed around the time of Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine. Since 2017 the increase has been almost linear. Source: NATO annual Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries reports 2011-2025[64].

Ukraine’s Failure Puts Further Onus on European Deterrence

If Ukraine collapses, costs bend sharply upward. NATO planners calculate that failure east of the Dnipro would require permanently stationing six heavy brigades in Poland, Romania and Slovakia at an annual cost above €30bn, plus a €12bn one-time infrastructure bill [65]. Forward deployed brigades demand ammunition, air-defence and logistics reserves that dwarf today’s support budgets.

The Kiel Institute’s cost-benefit model concludes that each euro spent on Ukrainian defence today offsets roughly €1.8 in future deterrence expenditure [2]. Even if the multiplier proves optimistic, the break-even point is far below current aid levels. In simple ROI terms, shells sent to Donbas generate higher security dividends than Abrams pre-positioned in Poland.

Can Europe fill America’s void?

Three trends, financial, industrial, and public support, suggest Europe’s capability to support Ukraine will continue to grow but only if political momentum holds. It is sobering to acknowledge, if the US were to stop all aid tomorrow Europe would unlikely respond quickly enough to replace all American support, or even have the capacity to do so. If Ukraine can hold its position this year, Europe’s growing arms production may allow Ukraine a notable advantage if US support reduces only modestly but does not cease.

Financially, collective European military aid has surpassed the U.S. and is anchored by multi-year EU bonds. There is scope for accelerating this support though this may partly need to take place outside of the joint programs conducted by the EU given the tepid support among some member states. It should not be ignored that the EU’s wealthiest nations, whose populaces strongly support Ukraine, have equally supportive leaders. This can also be said of the UK.

Industrial policy must keep up momentum. Programs like ASAP and the forthcoming European Defence Industrial Programme give manufacturers bankable demand. The time-line highlighted in this article for expanding production suggests that though this is far from ideal it remains a relevant time-frame for Ukraine’s continued defence. Delays, however, are no longer excusable.

There are weapons systems that Europe simply can’t produce, certainly not in quantity, that will require purchasing from the US. The time frame for this is measured in years before this can change. This is an uncertainty compounded by evidence of apparently fake "stock-takes" and US weapon hoarding.

On the part of the US this is no longer an issue of financial support but the willingness to sell weapons to its European allies in order to pass on to Ukraine. Additionally, intelligence sharing by the US remains critical with Europe only beginning to face the need for its own greater capabilities.

Other weapons systems not exemplified in this article mostly echo the increase in drone and shell production, Europe’s production is gathering pace with the question still remaining when the supply can satisfy Ukraine’s demand.

In regards to public support, majority support persists and despite a slight dip remains strong. Delivering visibly and sharing burdens equally are the keys to sustaining it. Russia’s persistent aggression must not be normalised. The media has a continued responsibility to inform.

Failure to resource Kyiv now would doom Ukraine and saddle Europe with a far larger, open-ended deterrence cost. The choice is stark, pay in shells today or pay in divisions tomorrow. Rearmament of Ukraine is both a moral obligation and the best return on investment.

[1] Reuters, “Europe races to fill Ukraine's ammo gap,” Reuters, 2024.

[2] K. I. for the World Economy, “Ukraine support tracker – April 2025 update.” 2025.

[3] European Defence Agency, “Annual defence data report 2023–2024.” 2024.

[4] F. Times, “Joe Biden pins blame for Russian battlefield victory on congressional inaction,” Financial Times, 2024.

[5] A. Press, “Analysis: A key withdrawal shows Ukraine doesn’t have enough artillery to fight Russia," AP News, 2024.

[6] B. News, “Ukrainian troops withdraw from avdiivka as ammunition shortage bites,” BBC News, 2024.

[7] Reuters, “Ukrainian troops withdraw from avdiivka as ammunition shortage bites,” Reuters, 2024.

[8] Reuters, “Zelenskiy urges leaders to plug ’artificial’ weapons shortage to stop Putin," Reuters, 2024.

[9] W. S. Journal, “Ukraine’s missile interception rate falls to 30% amid surge in Russian attacks,” WSJ (via Kyiv Post), May 2024.

[10] S. Bandouil, “WSJ: Ukrainian air interception rates decline amidst heightened Russian attacks,” Kyiv Independent, 2024.

[11] A. Shalal and M. Hunder, “Trump calls for immediate ceasefire,” Reuters, Dec. 2024.

[12] H. Lowell et al., “Hegseth falsely cited weapon shortages in halting shipments to Ukraine, democrats say,” The Guardian, Jul. 2025.

[13] Reuters, “Order by hegseth to cancel Ukraine weapons caught white house off guard,” Reuters, May 2025.

[14] Politico, “Republicans tear into Pentagon's Ukraine weapons freeze,” Politico, Jul. 2025.

[15] Reuters, “Trump says Russia and Ukraine to start immediate talks on ceasefire,” Reuters, May 2025.

[16] T. W. Post, "U.S. Pauses some Ukraine weapons shipments; Kyiv scrambles to respond,” Washington Post, Jul. 2025.

[17] A. Shalal and M. Hunder, “Trump says Ukraine will need patriot missiles for its defense,” Reuters, Jul. 2025.

[18] Reuters, “Germany’s merz spoke with Trump about buying patriots for Ukraine,” Reuters, Jul. 2025.

[19] Reuters, "U.S. Pauses key arms shipments to Ukraine pending review,” Reuters, 2025.

[20] Reuters, “Drone surges and ammo shortfalls: Ukraine’s supply strain,” Reuters, 2025.

[21] Reuters, “Germany’s Bundeswehr says only 68 % of promised marder IFVs cleared depots by May 2025,” Reuters, 2025.

[22] T. D. Post, “Italy’s aspide launchers delayed by four months,” The Defense Post, 2025.

[23] F. on the Arms Trade, “Poland ships home-built krab howitzers at four per month.” 2025.

[24] C. of the European Union, “Council greenlights up to €35 billion in macro-financial assistance to Ukraine," Council of the European Union, Oct. 2024.

[25] E. P. R. Service, “The European peace facility recapitalised to €17 billion.” 2024.

[26] NATO, “NATO leaders agree to raise defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035.” 2025.

[27] R. Staff, “EU military aid: Delays persist despite joint pledges,” Reuters, 2024.

[28] F. Times, “Polish and Czech firms ramp up artillery shell output amid Ukraine demand,” Financial Times, 2024.

[29] A. Council, “Why EU support for Ukraine remains more reliable than it seems,” Atlantic Council, 2024.

[30] D. Welle, “Germany signs contract for 105 leopard 2A8 tanks,” DW, 2025.

[31] UNN, “Raytheon doubles patriot production in Europe due to the war in Ukraine," UNN, Jun. 2025.

[32] Stars and Stripes, “First patriot missile facility outside US starts up in Germany," Stars and Stripes, Dec. 2024.

[33] Euractiv, “US patriot missile maker counts on Europe to increase missile production.” Jun. 2025.

[34] D. N. (via Financial Times), “Europe’s top missile maker MBDA boosts output 33% amid record orders.” Mar. 2025.

[35] F. Times, “Europe’s air-defence dilemma: Can franco-italian system rival US patriot?” Jun. 2025.

[36] W. S. Journal, “Ukraine’s war depends on musk’s starlink — and it’s a risk,” Wall Street Journal, 2024.

[37] Council of the European Union, "EUMA Ukraine extended and scaled.” 2024.

[38] UK Ministry of Defence, “Operation interflex reaches 56 000 graduates.” 2025.

[39] Ukrainian Presidential Office, “Zelenskyy–starmer talks on expanding training.” 2025.

[40] European Commission, “European defence fund 2025 work programme.” 2025.

[41] Reuters, “Romania opens regional f-16 training hub.” 2023.

[42] D. Peleschuk, “Ukraine aims to build one million drones in 2025.” 2025.

[43] D. M. of Defence, “Drone coalition commits 300,000 FPV systems for Ukraine." 2024.

[44] J. Adamowski, “Poland to quintuple FPV drone output for Ukraine." 2024.

[45] U. D. of Defense, “FY 2024–25 procurement programs (p-1): Unmanned aircraft systems.” 2024.

[46] M. Ajala, “Russia building major explosives facility as war drags on,” Reuters Investigates, 2025.

[47] S. Baker, “Russia on track to triple US-EU combined shell stockpile,” Business Insider, 2025.

[48] E. D. Agency, “ASAP ammunition production progress factsheet 2024.” 2024.

[49] E. D. Agency, “ASAP – projected shell output 2025.” 2025.

[50] F. T. Staff, “Europe’s defence-industry readies two million shells a year,” Financial Times, 2025.

[51] V. Insinna, “Army expects to make more than a million artillery shells next year,” Defense One, 2025.

[52] C. R. Service, “US industrial base for 155 mm artillery ammunition,” R48182, 2025.

[53] C. for Strategic and I. Studies, “Can South Korean ammunition rescue Ukraine?" CSIS Analysis, 2023.

[54] E. Commission, “Eurobarometer 103: Public opinion in the EU.” 2025.

[55] European Commission, “Around €2 billion to strengthen EU’s defence-industry readiness, including ramp-up to 2 million shells yr−1,” European Commission Press Release, 2024.

[56] “Flash eurobarometer 506 – EU solidarity with Ukraine." 2022.

[57] “Standard eurobarometer 101 – spring 2024.” 2024.

[58] “Standard eurobarometer 103 – spring 2025.” 2025.

[59] P. R. Center, “Majority of Americans continue to support sending weapons to Ukraine.” 2023.

[60] P. R. Center, “Public remains split over u.s. Assistance to Ukraine.” 2024.

[61] P. R. Center, “Americans’ attitudes toward aid to Ukraine, Feb 2025 update.” 2025.

[62] R. Maltezou, “Europe races to fill Ukraine's ammo gap,” Reuters, 2024.

[63] A. Gray, “EU military aid tops US for first time, says kiel tracker,” Reuters, 2025.

[64] NATO, “Defence expenditure of NATO countries (2010–2025) – series.” 2025.

[65] NATO, “Hague summit defence investment communiqué.” 2025.