Game Theory and Political Narratives: Using Quiet Non-cooperation to Combat Popularism

by u/ReasonRiffs

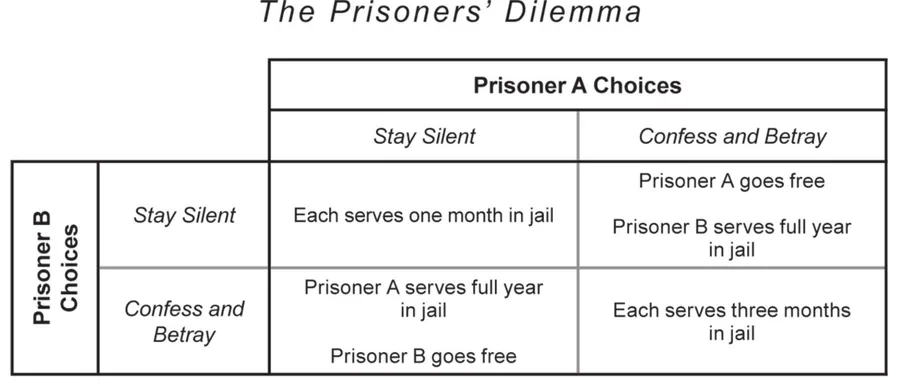

Majoritarian democracies such as the United Kingdom and the United States tend toward two-party competition, making political interaction unusually similar to iterated two-player games such as the reiterative prisoner dilemma [21,22].

Actions taken by one party are interpreted through a direct comparison with the other, and behaviour becomes legible as cooperation or defection (though can be expanded to include grades of tolerance and/or retaliation in more detailed models). Game-theoretic insights therefore carry unusual explanatory power in such systems, where the dynamics of reciprocity and conditional cooperation are in constant public view [1,2]. Yet any strategic move in politics is also a communicative act. A necessary instance of non-cooperation may be perceived as hostile retaliation if framed poorly, and overt rhetorical aggression can transform a measured strategic correction into an apparent act of vengeance. Studies clearly show this can bolster, not shrink support for populist parties [10,11].

This article attempts to bring together three strands of research in game theory, political communication, and research on populism. With the most advantageous strategies in game theory requiring reciprocity, the argument is made that effective political strategy requires quiet non-cooperation: a union of firm, reciprocal action with unvengeful framing. Such an approach maintains credibility, deters exploitation, and prevents populists from weaponising perceived victimhood [17,18] and thus the most effective strategy in combating popularism.

Effective Game-Theoretic Strategies in Noisy Political Environments

Game theory becomes most applicable where political interaction approximates repeated two-player dynamics. Proportional systems diffuse responsibility across multiple actors, generating a multiplayer environment with shifting coalitions and asymmetrical incentives. By contrast, majoritarian systems compress political conflict into dyadic form. The resulting symmetry and visibility of behaviour makes the underlying strategic structure particularly clear. The logic that governs successful strategies in repeated games therefore maps unusually well onto these political contexts [21,22].

Reciprocity is central to that logic. Axelrod’s work famously demonstrated that cooperation can emerge and persist when actors mirror one another’s moves [1,2]. Tit-for-Tat (TFT) was effective because it was retaliatory, forgiving, and clear. Nevertheless, in realistic settings (where signals are noisy, intentions cannot always be inferred, and occasional slips occur) strict mirroring alone is less effective. A single inadvertent defection may lead to a destructive cycle of retaliation [3]. More stable strategies allow minimal but essential tolerance for error, preventing accidental escalation while maintaining conditionality. Research on “tolerant” reciprocity shows that strategies which very occasionally forgive mistakes maintain higher rates of cooperation in noisy environments [7,8].

Yet even these more sophisticated strategies preserve one structural necessity: reciprocal non-cooperation when the opponent defects. As Fudenberg and Maskin demonstrated in their foundational analysis of the Folk Theorem, successful long-run cooperation depends on the credible threat of proportional retaliation [5]. Appeasement, that is continued cooperation in the face of persistent defection, is not a strategy but a failure of one. It forfeits influence over future behaviour and invites exploitation. Stochastic evolutionary models reiterate this point: strategies that refuse to reciprocate defection disappear quickly, even when intentions are good [8].

Moreover, the importance of reciprocity, and namely the critical act of reciprocal non-cooperation, can be seen in strategies that are both firm and noise-robust. Win–Stay, Lose–Shift answers losses with retaliation yet quickly restores cooperation when coordination is re-established, preventing vendetta loops while preserving deterrence [3]. Likewise, forgiving reciprocity (a variant of Tit-for-Tat) retaliates after defection but allows a small probability of immediate forgiveness, which stabilises cooperation under mistakes without signalling appeasement [7]. Stochastic models further show that such error-aware reciprocity improves upon rigid mirroring in noisy environments: strategies that never retaliate are exploited; strategies that strictly never forgive spiral into unproductive conflict [8].

In two-party democracies, reciprocal firmness is highly visible: it can read as credibility, while unconditional cooperation reads as weakness. Yet, as will be shown in the next section, research also warns that when combating popularism signalling non-cooperation too loudly can fuel grievance and invite misreadings of punishment. Facing non-cooperative behaviour (legislative obstruction, inflammatory rhetoric, or disregard for norms) still demands a proportional non-cooperative response, yet one that is signalled without spectacle and framed as procedural rather than punitive or vengeful. The strategic question is therefore not the mechanics/effect, but how to frame the response [10,11].

Populism, Victimhood, and the Rhetorical Logic of Conflict

Populism depends heavily on narratives of victimhood. Its emotional force derives from portraying “the people” as oppressed by corrupt elites, silenced and suppressed by institutions, and/or persecuted for speaking uncomfortable truths [15,16]. Affective political analyses show that feelings of humiliation and grievance are key mobilising tools for populist leaders, who position themselves as the sole defenders of an aggrieved public [17]. For example, studies of Central and Eastern European populist parties confirm that such actors routinely exploit narratives of historical and political injustice to legitimate their behaviour [19].

This reliance on victimhood means populists gain strength when mainstream actors appear punitive, contemptuous, or vengeful. Even measured criticism can be reframed as persecution. Research on communication and framing shows that perception, not intention, shapes political interpretation: how an act is framed influences how it is understood [11]. If mainstream actors respond to populist defection with visible outrage or rhetorical escalation, they validate the populist narrative of elite hostility. Emotional antagonism deepens polarisation, activating identity-protective cognition [12,13].

Conversely, studies on deradicalisation and political communication show that populists lose momentum when they are starved of emotional spectacle [14]. Quiet, consistent governance leaves little material for grievance amplification. Several empirical cases illustrate the point. In the Netherlands, populist gains flattened during periods where mainstream parties avoided rhetorical escalation and focused on policy delivery. In Germany, centrist actors often refused to engage rhetorically with AfD provocations, denying them the perceived persecution they sought [18]. Scandinavia offers similar examples: quiet competence undermines grievance-driven movements [20].

The pattern is consistent across systems: populism depends on antagonistic reciprocity. Remove the visible antagonism, and its emotional architecture weakens [15,16,17].

Quiet Non-cooperation, Strategy Without Spectacle

This section aims to marry the act of non-cooperation from game theory with research on popularism.

Quiet non-cooperation emerges from combining game-theoretic logic with the psychology of populist communication. Strategically, reciprocal non-cooperation is essential for credibility and long-run cooperation [5]. Politically, punitive rhetoric strengthens the very forces that reciprocal action seeks to constrain [17,18]. Quiet reciprocity therefore seeks to preserve firmness while neutralising the emotional charge of retaliation.

Consider this chess analogy. When a player maneuvers s themselves into a weakened position whether overextended or structurally compromised, commentary typically attributes their predicament to their own earlier decisions. The opponent’s strength and moves matter, but the narrative centres on the errors that created vulnerability. The victorious player need not proclaim any strategic brilliance even when significant in the outcome.

Quiet non-cooperation operates on the same principle. When a populist movement manoeuvres itself into contradiction or irresponsibility, the response/framing should highlight the chain of decisions that led to the current situation, not its own strategic blocking. Meanwhile political acts of reciprocal non-cooperation should be at play that can fit within this narrative. Firmness is depersonalised. Responsibility is shifted, accurately, to the actors who created the difficulty. The political actor remains strategically steady while rhetorically calm, denying the populist movement the emotional oxygen of spectacle.

The key tenets of quiet non-cooperation

• Reciprocal non-cooperation is enacted when necessary. This can be framed, for example, as institutional responsibility rather than punishment, as the only counter action that could be taken, or distracted from where needed. [10,11].

• Rhetoric remains measured, factual, and unvengeful, possibly inevitable, minimising opportunities for grievance amplification [11,14].

• Explanations emphasise the opponent’s actions leading to their predicament, not one’s own firmness.

• Openness to future cooperation is maintained, keeping conditionality clear without signalling hostility [7]. Cooperation itself need not be quiet and can play a role in mitigating the victimhood framing of populist ideology.

• Emotional spectacle is avoided; populists are denied the theatre required for victimhood performance [17,19].

Thus quiet non-cooperation avoids appeasement without provoking escalation. It maintains positional integrity in the game-theoretic sense while suppressing the narrative dynamics that empower extremism.

As such an overarching political strategy can hybridise game theory strategies, such as Win–Stay, Lose–Shift, with rhetorical framing guided by research on popularism. Thiis is not an argument for the specific game theory strategy employed whilst recognising each effective strategy requires reciprical non-cooperation. Hence, quiet non-cooperation is demonstrated to be a fundamental act in responding to a populist party. Upon experiencing examples of cooperation, reciprocal acts of cooperation may be employed but needn’t be quiet. To the contrary vocalised cooperation may indeed mitigate the victim narrative of the populist party.

Practical Examples in the US and UK

This section is a brief overview of examples of quiet non-cooperation, contrasted by appeasement where quiet non-cooperation would have been the more effective reciprocal response.

In the United States, the autumn 2025 funding stand-off/government shutdown reads very closely as an excellent example of quiet non-cooperation. Democrats declined a stop-gap they judged would undercut Affordable Care Act subsidies, kept their language procedural (“extend the tax credits, follow regular order”), and let the institutional timetable do the heavy lifting while observing public opinion. Polling showed more blame accruing to Republicans than to Democrats overall, with independents particularly lopsided. Other reputable polls apportioned blame more broadly but still put Republicans ahead [23,24,25]. The framing as well as the effect likely played a major role in the Democrats electoral success at the end of 2025.

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Additionally, in the United Kingdom, the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019. To clarify, the Tory government of the time was lead by Boris Johnson whose leadership was populist in approach. The act, also known as the Benn Act and put forward by the opposition, offers a clean example of reciprocal non-cooperation framed as rule compliance rather than reprisal. Such a maneuver whilst being in opposition can make effective non-cooperation more challenging, making this all the more impressive. Cross-party MPs seized control of Commons time and compelled a letter seeking an Article 50 extension. Ministers sought to recast it as a “Surrender Act,” but the legal duty stood and was executed [26,27].

This act of quiet non-cooperation was continued by a further illustration. Opposition parties initially refused an early general election under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act whilst calmly calling for no election until the extension is secured and keeping attention on procedure, not theatre [28,29,30]. Arguably these acts helped contain the premiership of Boris Johnson.

Yet, there are various cases where quiet non-cooperation could have been applied but wasn’t. The US 2011 debt-ceiling confrontation stands out as an example, though marginally applicable given that the Republicans were arguably on the cusp of popularism at the time. In 2011, a newly elected Republican House majority used the statutory debt limit as leverage, refusing a clean increase unless the Obama White House accepted multi-year spending cuts. The resulting Budget Control Act (BCA) raised the ceiling in stages, imposed decade-long discretionary caps, created a bipartisan super committee, and, after that=9im k failed, triggered automatic cuts [31,32,33]. In substance, Republicans extracted concessions in exchange for lifting the ceiling. A quiet-non-cooperation alternative would have refused policy concessions under threat insisting that a clean increase was routine fiscal housekeeping thus raising the expected cost of hostage tactics while keeping the rhetoric strictly procedural [31,32,33]. Instead, this act of appeasement began a practice that then became expected.

A second US example arose in 2024 with the “border-for-Ukraine” package. The White House backed a sweeping Senate package that paired Ukraine/Israel aid with tougher asylum rules (including an emergency shut-off authority) as a compromise to entice Republican votes. Yet house leadership then declared the deal “dead on arrival,” and Senate Republicans blocked it. Substantive concessions were offered before reciprocal cooperation materialised, producing a one-sided outcome [41,42,43]

A quiet non-cooperation alternative would have recognised the non-cooperative stance of the Republicans whilst giving the impression of a willingness to see no package succeed if too many compromises are made. First, decouple the issues and insist on separate, clean votes (security assistance on its own calendar, border policy on its own track), justified as adherence to regular order rather than as a partisan dare (neutral framing). Second, prepare effective rule-based workarounds if leadership stonewalls, presented as neutral institutional safeguards rather than leverage. Third, communicate in a strictly procedural frame, “we do not rewrite long-standing immigration statutes under threat linkage; aid bills receive a clean vote, and statutory reform, if any, runs the normal committee process.” Finally, attribute outcomes to choices, not motives: if aid is blocked, say so plainly and move the clean bill again; if counterparts engage on border reform, negotiate with published text and hearing schedules. The contrast is that the bargain offered policy concessions upfront, inviting non-reciprocation, whereas quiet non-cooperation strictly withholds concessions under linkage, keeps pressure via rules and calendars, and denies the grievance theatre that thrives on visible brinkmanship [41,42,43].

These two US examples are not decoupled. Years of intermittently appeasing Republicans have taught them that Democrats will yield, as they did in 2024. This means that signalling of a new more effective strategy requires greater consistency than if it had been adopted earlier. The implementation of such a strategy will thus experience, at first, reciprocity that will be highly non-cooperative making quiet non-cooperation an indispensable tool to avoid Republicans claiming themselves as victims. Strict adherence will however lead eventually to mutual cooperation with a likely simultaneous vanquishing of the Republican’s current populist nature.

Evidence of similar submissive behaviour in the context of the UK can be seen with regards to the Article 50 Brexit legislation in 2017, predating the examples of quiet non-cooperation given above. The House of commons voted by a large margin to trigger the exit from the EU after the Supreme Court confirmed Parliament’s role. The opposition, lead by the then Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, largely accepted the Government’s timetable and framing, imposing only limited, non-binding conditions on the negotiations.

Following a quiet-non-cooperation methodology would have been to condition consent procedurally at every single step, such as binding guarantees on EU citizens’ settled status before negotiations, or explicit, staged tests on single-market and customs-union options. This could have easily been framed as safeguarding an orderly exit rather than obstructing it [36,37]. Instead the eventual outcome was nearer to a hard Brexit than one of compromise which would have been a more honest reflection of the 51-49 Referendum vote.

Today in the UK the populist opposition, led by Reform (and fringes of the Tory party) do not hold political power. This is a clear opportunity to enact strict quiet non-cooperation in response to their abrasive rhetoric and weaponisation of migration. Yet, the current Labour leadership appears uninformed in regards to how populism is combatted, including investment in poorer communities [44,45] instead demonstrating the strategically inept act of appeasing popularism.

Meanwhile in the United States, Democrats in opposition, thus short on formal levers, have shown how quiet non-cooperation can work. If they keep to their strategy of reciprocity, adding only what procedure requires and framing every consequence to Republican choices, the endgame writes itself: Republicans walk into their own compulsion to move, and when the check mate arrives it can be framed as the inevitable result of their moves, not Democratic malice.

Bibliography

[1] Axelrod, Robert “The Evolution of Cooperation” (1984)

[2] Axelrod, Robert The Complexity of Cooperation (1997)

[3] Nowak, Martin A., & Sigmund, Karl. “A Strategy of Win–Stay, Lose–Shift.” Nature Journal (1993)

[4] Nowak, Martin A. “Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation.” NiH (2006).

[5] Fudenberg, Drew, & Maskin, Eric. “The Folk Theorem in Repeated Games with Discounting or with Incomplete Information” Econometrica (1986).

[6] Selten, Reinhard, & Hammerstein, Peter. “Gaps in Harley’s Argument on ESS.” (1984)

[7] Boyd, Robert. “Mistakes Allow Evolutionary Stability in the Repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma Game.” Journal of Theoretical Biology (1989)

[8] Imhof, Lorens A., & Nowak, Martin A. “Stochastic Evolutionary Dynamics with Strategic Mistakes.” Journal of Theoretical Biology (2010)

[9] Lakoff, George. Moral Politics. University of Chicago Press (2002)

[10] Goffman, Erving. Frame Analysis. Harvard University Press (1974)

[11] Entman, Robert. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” (1993)

[12] Sunstein, Cass R. #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media Princeton University Press (2017)

[13] Iyengar, Shanto, & Westwood, Sean J. “Fear and Loathing Across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization.” (2015)

[14] Druckman, James N., & Nelson, Kjersten R. “Framing and Deliberation Effects.” American Journal of Political Science (2003)

[15] Mudde, Cas. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press (2017)

[16] Mols, Frank, & Jetten, Jolanda. Understanding Support for Populist Radical Right Parties (2020)

[17] Homolar, Alexandra, & Löfflmann, Georg. “Populism and the Affective Politics of Humiliation Narratives.” Global Studies Quarterly (2021)

[18] Cianciara, Agnieszka K. “Victimhood as a Legitimation Strategy of Populism in Power: The Case of Poland.” Contemporary European Politics (2025)

[19] Meijen, Jens, & Vermeersch, Peter. “Populist Memory Politics and the Performance of Victimhood.” Cambriddge Press (2023)

[20] Eatwell, Roger, & Goodwin, Matthew. National Populism, The Reovolet Against Liberal democracy (2018)

[21] Duverger, Maurice. Political Parties (1954) [Still very much a relevant text]

[22] Cox, Gary W. Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World’s Electoral Systems. Cambridge University Press (1997)

[23] Washington Post–ABC News–Ipsos. “Americans blame Trump and GOP more than Democrats for shutdown” (Oct. 30, 2025)

[24] Reuters/Ipsos. “U.S. government shutdown threatens spending power of congress” (Oct. 26, 2025).

[25] AP-NORC Center. “Most see the federal shutdown as a problem and think there is plenty of blame to go around” (Oct. 16, 2025).

[26] Institute for Government. Benn Act / EU Withdrawal (No. 2) Act - Explainer (Sept , 2019)

[27] House of Lords Library / UK Parliament. UK’s Withdrawal from the European Union: Briefing for the Benn Act (Oct. 19, 2019)

[28] UK Parliament (parliament.uk). “MPs vote against motion for an early general election” (Sept. 4, 2019)

[29] The Guardian. “Boris Johnson fails in third attempt to call early general election” (Oct. 28, 2019)

[30] House of Commons Library. The Fixed-term Parliaments Act (Jan. 14, 2020)

[31] Congressional Research Service. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (report number: R41965, Aug. 19, 2011)

[32] Congressional Research Service. The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects (report number: R42506, Dec. 29, 2015)

[33] Congressional Research Service. Budget “Sequestration” and Selected Program Exemptions and Special Rules (R42050, June 13, 2013)

[34] ABC News. “Senate fails to change filibuster rule for passage of voting rights legislation” (Jan. 19, 2022)

[35] PBS NewsHour / AP. “Voting rights bill blocked by Republican filibuster” ( 2022)

[36] Hansard (UK House of Commons) European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill Second Reading: Division 135 (2017)

[37] TIME. “The U.K. Supreme Court’s Brexit Ruling:What to Know ” (2017)

[41] Associated Press. “Senators release a border and Ukraine deal but the House speaker declares it ‘dead on arrival’ ” (Feb. 2024)

[42] PBS NewsHour. “What’s in the Senate’s sweeping $118 billion immigration and foreign aid bill?” (Feb. 2024)

[43] The Guardian. “Senate Republicans block bipartisan border security bill for a second time” (. 2024).

[44] Gold, Robert “Paying Off Populism: How Regional Policies Affect Voting Behavior.” (2025).

[45] Foster, Chase “Compensation, Austerity, and Populism: Social Spending and Electoral Support for Populist Parties.” [Working paper] (2022)