Putin’s Links to European Far-Right Networks

by u/ReasonRiffs

In a previous article evidence was given of how soviet misinformation campaigns targeted destabilising western democracies through the propagation of lies such as AIDs being created by the CIA. More sinister was the drive to fund and bolster the far-right political movements which can be seen to this day across Europe. Rather than an opportunist act, this act of aggression on the fabric of democracy was, and is, premeditated.

This article aims to draw the readers attention to Vladimir Putin’s personal history and efforts in this campaign by the KGB to strengthen the far-right in western democracies, and how this shapes our understanding of the motivations behind the various examples of Kremlin funding today’s far-right torch bearers. This exemplifies one of the greatest threats to our democracies.

Putin’s Pre-Dresden Years in Leningrad

After graduating from the KGB’s Yuri Andropov Red-Banner Institute in 1984, Putin returned to his home city and served in the Leningrad & Leningrad Oblast KGB Directorate, Second Chief Directorate (counter-intelligence). Contemporary personnel files and biographical interviews place him in Department 3, responsible for monitoring foreigners, recruiting informants in universities, and vetting Soviet citizens with access to visitors [24][25]. Former colleagues told investigative reporters that Putin’s day-to-day work centred on “spotting and assessing” foreign students and consular staff, cultivating rezidenty (local sources) inside Leningrad State University, and writing analytical notes on Western diplomatic traffic [24][26].

The Leningrad Directorate itself had a longstanding remit for ‘active measures’: disinformation against political refugees, covert influence on visiting trade delegations, and logistical support to Service A (the First Chief Directorate’s global active-measure arm) when operations transited the Baltic ports [27]. It is important to note that strategic decisions to exploit the far-right were drafted at First Chief Directorate Service A in Moscow and implemented later by residencies such as Dresden. While no open file shows Putin personally running black-propaganda operations at this stage, he worked inside an office that fed manpower and cover logistics into the KGB’s broader subversion toolkit in conjunction with Service A. Masha Gessen cites a retired officer recalling that Leningrad produced “ready-made document sets” for illegal operatives and occasionally staged “provocations” against foreign sailors , similar to tactics later honed in Dresden [25].

It was already clear at this stage that Putin had links with Service A, the department responsible for the soviet strategy of weaponising neo-Nazi movements in western-Europe.

The Briefest History of the Soviet Service A’s Neo-Nazi Support and Related Activities

The Soviet Union’s Service A (the KGB’s active-measures department, renamed from Department D in 1964) began by planting fake “Nazi scandals” to blacken Bonn’s reputation, the then capital of West Germany. By the late 1970s it crossed a far more consequential line, it put neo-Nazis on the payroll and began their weaponization against democracy.

The following list illustrates cases that are currently known of direct support for neo-Nazis. Germany in particular exemplifies the evolution from fear mongering to actual intent to manifest greater far-right sentiment.

Germany:

- Directive 11/78 A top-secret circular from East Germany’s HVA explicitly authorised “co-operation with selected extreme-right activists in the FRG,” budgeting travel cash and safe flats to “compromise Bonn domestically and abroad” [28].

- Hepp-Kexel, 1981-82 Archival files and court records prove that Stasi Section XXII and the Dresden rezidentura (residences/hubs) gave cash, blank passports and a Berlin safe house to Odfried Hepp’s neo-Nazi terror cell, directing its violence toward U.S. military targets to embarrass NATO [29].

- WSG Hoffmann & ANS/NA, 1983-85 Stasi report XV/1289 logs quarterly “operative subsidies” (approx. 2 000 Deutsch Mark) for fugitives from Wehrsportgruppe Hoffmann; a 1984 KGB cable to Dresden instructed continued support to Michael Kühnen’s ANS/NA network, conditional on steering attacks away from Soviet assets [30].

Austria:

- VAPO (Volkstreue ausserparlamentarische Opposition), 1987-89 Prague’s StB file XV/21515 “BURAN” shows forged Austrian passports and travel stipends funnelled to Gottfried Küssel’s Volkstreue Außerparlamentarische Opposition under joint StB–Stasi supervision [31].

Belgium

- WNP (Westland New Post), 1984 HVA inquiry Anfr. 127/84 labels Stéphane Busiarine of Westland New Post a far-right organisation, “penetrable” and proposes a bursary; no follow-up disbursement is on record [32].

Italy

- NAR (Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari) exiles, 1983-85 Romanian (then communist) security cables (cited by Italy’s Mitrokhin Commission) describe safe transit and living expenses for former members of the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari en route to Syria, “in co-ordination with KGB Service A for exploitation against NATO narratives.” The evidence rests on Romanian summaries rather than original KGB files, but it shows intent beyond the German sphere [33].

By 1987, when Putin was honing the same craft in Dresden, Service A had evolved from forging Nazi archives to funding live neo-Nazi cells in at least three West-European countries.

Dresden’s Playbook: Neo-Nazis, Terrorists, and the Birth of a Strategy

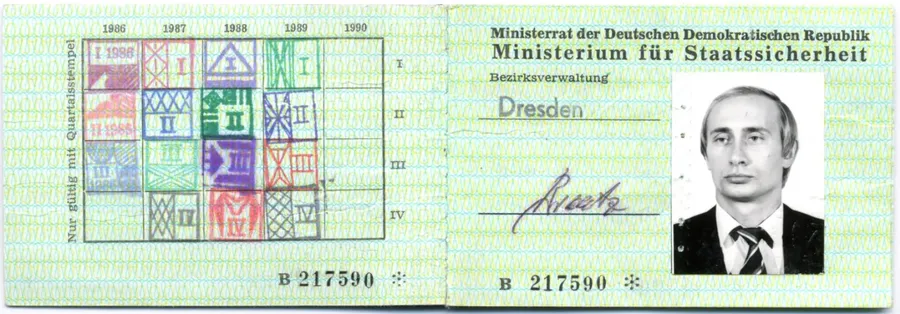

When Vladimir Putin arrived in Dresden in 1985, the provincial backwater on the Czech border turned out to be a significant hub of active measures. As a KGB officer seconded to the Stasi, he held an East-German secret-police ID card granting him full access to Stasi offices and archives [1]. His unit’s mandate was classic active-measures work - destabilising NATO countries by cultivating extremists and proxy actors.

Archival research shows that the KGB-Stasi Residentura on Angelikastraße 4, where Putin was based, cooperated with Odfried Hepp’s Hepp-Kexel terrorist network, supplying safe houses, forged papers and escape logistics for militants who robbed banks and attacked U.S. targets [2]. Parallel Stasi files, examined by Andreas Förster and others, confirm infiltration and steering of Wehrsportgruppe Hoffmann (WSG), Michael Kühnen’s ANS/NA, the FAP, and the Wiking-Jugend [3,4,5]. The aim was not ideological sympathy but weaponisation. Exploit any radical milieu that could damage Bonn (the then capital of West Germany) and erode Western cohesion.

A former Stasi defector interviewed by journalist Catherine Belton later alleged that Putin personally handled “a notorious neo-Nazi … who helped stoke the rise of the far right in the East.” [6] Subsequent investigative work identifies that neo-Nazi as Rainer Sonntag, a militant who indeed collaborated with the Stasi and was active in Kühnen’s ANS/NA network before returning to Dresden after reunification, where he organised violent gangs until his sudden death in 1991[7]. While Putin’s direct supervision of Sonntag is only confirmed through anonymous sources, the surrounding evidence, that Dresden’s KGB–Stasi cell did run far-right assets , is firmly established [2–5].

The Mitrokhin Archive confirms the doctrinal logic. KGB manuals instructed rezidenturas to infiltrate both far-left and far-right groups as interchangeable instruments of destabilisation [8]. Dresden was the laboratory for that doctrine, and it formed the professional culture that clearly shaped Putin’s worldview.

The Kremlin’s Currently Known (European) Far-Right Network

Three decades later, the same methodology is visible across Europe evolving into a grasp for power. The pattern is consistent, financial lifelines from Kremlin-linked banks, oligarchs, or energy firms to nationalist movements that echo Moscow’s foreign-policy narratives and self destructive policies that weaken the countries within which they are based.

Here are but a few verified examples:

Country / Party | Verified or Strongly Evidenced Kremlin Link | Key Sources |

|---|---|---|

France – National Rally | 2014 loan (€9.4 m) from the Kremlin-aligned First Czech-Russian Bank, later transferred to defence contractor Aviazapchast; the loan kept Le Pen’s party solvent. | GMF/ASD [9]; Reuters 2020 |

Italy – Lega | 2019 Moscow Metropol tapes record Salvini aides discussing a discounted Rosneft oil scheme to funnel campaign funds. Recording verified; investigation archived without charges. | FT, Reuters 2019; ASD [10] |

Austria – FPÖ | 2016 five-year “co-operation pact” with United Russia; 2019 “Ibiza video” shows readiness to accept covert Russian money for contracts & media. | ASD [10]; Reuters 2016 |

Germany – AfD | 2024 Voice of Europe scandal: EU-sanctioned site run by Viktor Medvedchuk paid MEPs to spread anti-Ukraine propaganda; investigations named figures linked to AfD. | Reuters 2024 [11] |

Hungary – Fidesz | €10 billion Russian state loan (2014) for Paks II nuclear plant – approx. 80 % of cost – embedding Moscow’s energy tentacles into Budapest. | CEPA [12] |

UK – Brexit / Reform orbit | Financier Arron Banks met Russian Embassy officials ≥11 times (2015–16) while exploring gold & diamond ventures; donated £8 m to Leave EU and funded Farage; Parliament said he misled MPs about Russian contacts. The Brexit campaign won by a paper thin margin causes immense economic damage. | UK Parliament DCMS [13–14] |

Each case is documented by contracts, sanctions, or court proceedings. The form varies - loan, commodity scheme, influence platform - but the function is constant: fund the far-right voices that fracture the West.

Personnel Continuity: From Dresden to Today’s Parties

In Germany, the AfD’s hard-right wing carries visible lineage from earlier extremist networks. Andreas Kalbitz (expelled 2020) belonged to the banned Wiking-Jugend, and Björn Höcke ( AfD leader in Thuringia) allegedly wrote under the pseudonym Landolf Ladig for NPD-linked journals, a conclusion shared by several press and intelligence assessments [20–21]. Jens Maier, ex-AfD MP, was fined after quoting an SS song at a 2024 party event still sung by neo-Nazi groups in Germany [21]. These continuities show that post-war neo-Nazi subcultures still seed the parliamentary far-right - milieus once infiltrated by the Stasi in the 1980s [3–5].

Austria’s FPÖ and Italy’s Lega exhibit similar overlaps, youth-wing figures from nationalist or skinhead circles now serve as officials [10]. These examples suggest ties maintained over decades have likely played a role in establishing trust between the far-right parties and their Russian backers. Moreover, that this is not an act of opportunism on the part of the Kremlin but a long term strategy.

The Trans-Atlantic Echo: Trump and the Russian Mafia

Donald Trump’s involvement with the Kremlin mimicks that of the known European assets.

In 1987 Soviet ambassador Yuri Dubinin invited Donald Trump to Moscow on a trip organised through channels often used by the KGB to court Western businessmen. Soon thereafter, Trump suddenly took out full-page newspaper ads urging the U.S. to scale back its NATO commitments and promoting tariffs and an isolationist approach - precisely the line Moscow favoured [22].

At the junction of Russian state and organised crime stands Semion Mogilevich, described by the FBI as “the most dangerous mobster in the world.” known for billion dollar fraud. Despite international warrants, Mogilevich has lived freely in Moscow for decades, briefly detained on minor tax charges in 2008 and released in 2009 [17].

Analyses of Galeotti’s Global Crime study and ECFR’s Crimintern report explain this as a mutual-protection economy: criminals provide cash and overseas logistics; Russian state actors guarantee impunity [18–19]. Despite there is no public proof that Mogilevich takes orders from the Kremlin, the pattern of sanctuary and cooperation fits that model precisely.

Financially, one of the clearest Kremlin-Trump links is through his business with Mogilvich. In 1984 Russian-mob associate David Bogatin, linked to Mogilevich’s network, purchased five Trump Tower condos for $6 million. U.S. authorities later seized them as laundering assets [23]. Through the 1990s and 2000s Russian capital via the Bayrock Group and other intermediaries financed Trump projects when American banks would not. Investigations by journalists such as Luke Harding and Craig Unger document these flows [22–23].

In isolation this evidence of Trump’s links with the Kremlin may be doubted, yet when considered as part of the broader body of evidence in Europe the question becomes; What is the degree and depth of control that the Kremlin continues to directly have over Trump, not whether it exists at all.

Active Measures Remain Active, the Greatest Threat to our Democracies

The chain of evidence is now clear, the Kremlin interferes with various West democracies with arguably greater destructive success than on the battlefield. Putin’s direct experience in the soviet methods of the 1980s, and his support for far-right actors in today’s Europe, show a continuity of strategy in contrast to what might be seen as opportunist ad-hoc actions. These far-right parties encourage the electorate to favour policies of insular inward looking politics that is toxic to alliances such as NATO and a form of fascistic thinking completely opposed to liberal democracy.

Despite the modernisation of financing methods evidence still exists for a breadth of ongoing activities, despite the fact that there are likely various examples that go uncovered. It is unsurprising that assets developed during the soviet era may indeed be playing a role in the current manifestation of the Kremlin’s anti-Western, anti-democratic agenda.

Yet, despite the threat to our democracies a great swath of the public remain unaware, uninterested, or in the worst case in denial of the threat. In turn, this leads to often mediocre punishments once crimes are apparent, and little drive from governments to truly investigate and punish politicians with likely links to the Kremlin.

As immense damage continues to be done to our democracies (such as the economic damage of Brexit or the tainting of political debate and discussion) it is reasonable to question whether the response will become ever more inadequate or whether there will finally be a reckoning with what amounts to political warfare against the heart of our democracies.

Bibliography

[1] Reuters. “Putin’s Stasi identity card discovered in German archives.” 11 Dec 2018.

[2] Blumenau, Bernhard. “Unholy Alliance: The Connection between the East German Stasi and the Right-Wing Terrorist Odfried Hepp.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 43, no. 1 (2020): 47–68. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2018.1471969.

[3] Förster, Andreas. Zielobjekt Rechts: Die Stasi und die Neonazis. Berlin: Links Verlag, 2018.

[4] Lee, Martin A. “Strange Ties: The Stasi and the Neo-Fascists.” Los Angeles Times (Op-ed), 10 Sept 2000.

[5] Förster, Andreas. “Stasi bespitzelte die rechte Szene im Westen.” Stuttgarter Zeitung, 7 Aug 2015.

[6] Belton, Catherine. Interview by Heike Buchter and Michael Thumann. “Putin was supposedly also a handler of a notorious neo-Nazi.” DIE ZEIT, 7 July 2022.

[7] Williams, Steve. “The Man Behind the Curtain.” SourceMaterial Magazine, 2022.

[8] Andrew, Christopher and Vasili Mitrokhin. The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. Penguin, 2000.

[9] Alliance for Securing Democracy (GMF). “First Czech-Russian Bank Case Study.” 2018.

[10] Shekhovtsov, Anton. Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir. Routledge, 2017.

[11] Reuters. “EU sanctions Voice of Europe and two businessmen over Russian disinformation.” 27 May 2024.

[12] Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). “Russia Finances 80 Percent of Hungary’s Paks II Reactor.” 2021.

[13] UK Parliament. DCMS Committee: Disinformation and ‘Fake News’ – Interim Report. HC 363 (2018).

[14] UK Parliament. DCMS Committee: Disinformation and ‘Fake News’ – Final Report. HC 1791 (2019).

[15] FBI. “Semion Mogilevich.” Ten Most Wanted Archive.

[16] U.S. Department of Justice. Indictment of Semion Mogilevich et al., YBM Magnex case, E.D. Pa., 1998.

[17] OCCRP. “Moscow Releases Mogilevich.” 29 Oct 2008.

[18] Galeotti, Mark. “The Criminalisation of Russian State Security.” Global Crime 7, no. 3–4 (2006): 475–496.

[19] Galeotti, Mark. Crimintern: How the Kremlin Uses Russia’s Criminal Networks in Europe. European Council on Foreign Relations Policy Brief, 18 April 2017.

[20] Verfassungsschutz Brandenburg. Annual Report 2019 (entry on Andreas Kalbitz / Wiking-Jugend).

[21] Oberverwaltungsgericht Berlin-Brandenburg (Kalbitz decision, 2020) and press coverage including Die Welt (June 25, 2024) and The Guardian (2021–2024) on Höcke, Kalbitz and AfD disciplinary cases.

[22] Harding, Luke. Collusion: Secret Meetings, Dirty Money, and How Russia Helped Donald Trump Win. Faber & Faber, 2017.

[23] Unger, Craig. House of Trump, House of Putin. Doubleday, 2018.

[24] Belton, Catherine. Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West. HarperCollins, 2020.

[25] Gessen, Masha. The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. Penguin, 2012.

[26] Soldatov, Andrei and Irina Borogan. The New Nobility: The Restoration of Russia’s Security State. PublicAffairs, 2010.

[27] (Replaced erroneous entry) Galeotti, Mark. Crimintern: How the Kremlin Uses Russia’s Criminal Networks in Europe. ECFR Policy Brief, 2017.

[28] Bundesarchiv BStU. HVA Directive 11/78, reproduced in Förster, Zielobjekt Rechts (2018), Appendix A, pp. 302–304. (Archival source cited in secondary literature)

[29] same as [2]

[30] Andrew, Christopher and Vasili Mitrokhin. The Sword and the Shield. Basic Books, 1999. Stasi file XV/1289 cited in Förster, pp. 217–219.

[31] StB Archive, Prague. File XV/21515 “BURAN” (declassified 2014); cited in Förster, Zielobjekt Rechts, pp. 219–222. (Archival source)

[32] HVA memo Anfrage 127/84. Cited in Serge Vande Walle, “Les Faschos et l’Est.” Revue Nouvelle 5 (2002), p. 12. (Archival reference via secondary source)

[33] Italian Parliament. Mitrokhin Commission Final Report, Annex F (2003). (Commission report; secondary citations widely used)